Editing for Success: An Inside Look at the Career of Film Editor Mr. Ju

The film and entertainment industry has undergone a significant transformation over the last few decades. It has grown from a niche sector into a major global powerhouse that touches billions of lives daily. The industry’s creative, economic, and social significance cannot be understated, with its influence reaching far beyond entertainment. In today’s digital age, it not only shapes pop culture and societal narratives, but also drives technological innovation and economic growth.

At the heart of this influential industry are the talented individuals who breathe life into stories, and one such individual is Haoyu Ju. A renowned film editor, Ju has etched his name in the annals of contemporary cinema through his outstanding body of work. His creative vision and technical mastery have seen him work on an array of films, several of which have been lauded at respected film festivals worldwide.

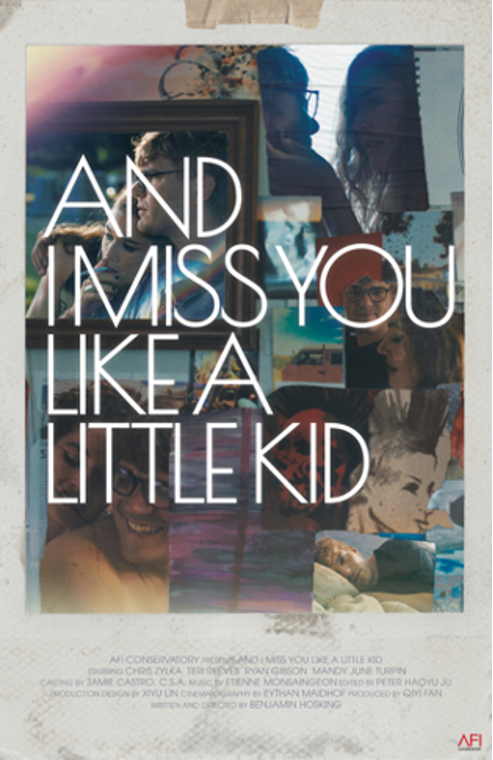

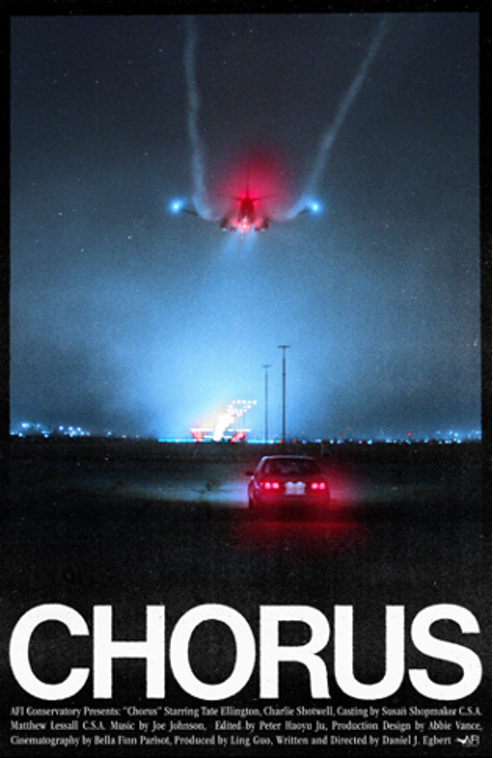

Ju’s story began at the American Film Institute Conservatory, where he honed his skills and developed a keen eye for narrative construction. Since then, his career has been a testament to his craft, with films such as “CHORUS” and “AND I MISS YOU LIKE A LITTLE KID” receiving critical acclaim and festival recognition. His editing prowess has not only shaped these films but also contributed to the broader discourse on cinematic storytelling.

His work in “CHORUS” was singled out for its narrative clarity and emotional resonance, a testament to Ju’s ability to sculpt narratives that deeply engage viewers. Similarly, his work in “AND I MISS YOU LIKE A LITTLE KID” has demonstrated his aptitude for handling complex themes with sensitivity and finesse. These films’ successes at prestigious platforms like the New York Shorts International Film Festival, CAA Moebius, and AFI Fest underscore Ju’s industry standing and his continued relevance in contemporary cinema.

We had the unique opportunity to converse with Haoyu Ju, peeling back the curtain to his creative process, career journey, and understanding of the industry. Over the course of our discussion, we delved into his philosophies, methodologies, and vision for storytelling in the 21st century. From his creative inspirations to his approach to editing and his thoughts on the future of the film industry, our conversation with Ju provided fascinating insights into the mind of one of today’s most accomplished film editors.

You’re such an inspiration to a lot of people. Tell us, what drew you to become an editor in the film industry and how did you get started?

Much like filmmakers who have their first taste of filmmaking when they pick up a camera and press record, my journey into the realm of editing started when I laid my fingers on the keyboard of my laptop. This was during a video class in my undergraduate years at UCLA, where I had the opportunity to edit the first video I had ever shot myself.

Following that initial experience, a three-year residency ensued. This period was characterized by intensive practice and study of filmmaking and editing. I had the chance to collaborate with numerous filmmakers, honing my skills through cutting a variety of films. This intense period of growth and development allowed my qualifications, knowledge, and skills as an editor to mature exponentially.

Now, I find myself joining the ranks of thousands of other editors in Hollywood, all of us united by our shared passion for storytelling. But, as is true with any artistic craft, editing is a journey that extends over a lifetime. I have just taken my first steps, and I am eager and excited for the road ahead.

In your opinion, what are some of the most important qualities for an editor to have, and how have you developed these qualities throughout your career?

Renowned Oscar-winning editor Richard Halsey once paid a visit to my editing class at the AFI Conservatory. During his enlightening session, he outlined three key principles of an editor: organization, trusting your instincts, and truth-telling. These words have since served as guiding tenets in my editing practice.

We often describe editing as the final draft of a film, signifying the immense responsibility it holds. An editor weaves together pictures and sounds, shaping the story into its most compelling form. The task is delicate; editing can either elevate a film or bring about its downfall. An editor’s choice, whether it concerns the length of a cut, the type of shot for a beat, or the selection between a classical music piece or a rock song, can have substantial consequences.

This challenging task demands an editor with keen acuity, meticulous attention to detail, superior technical proficiency with NLE programs, an indomitable spirit for trial and error, and most importantly, a comprehensive understanding of the story and its characters.

Interestingly, the fate of a film often hinges on the dynamics within the editing room. As the first audience of the film, an editor must provide honest feedback about the effectiveness of the story’s portrayal while working alongside the director, producer, or executives. The final outcome of a film is always a matter of uncertainty. However, through diplomatic collaboration, effective communication with fellow filmmakers, trust in one’s instincts, and commitment to truth-telling in the editing room, a film can find its most promising path.

You have worked on several films that have been featured in prestigious film festivals around the world. What advice would you give to up-and-coming editors?

As an editor working in a below-the-line role, my primary duty is to let the stories of others flourish. There’s something deeply fulfilling about contributing to a project that you genuinely admire and care about. Regardless of the stage at which I join a production, whether during development or after principal photography, the first crucial task is to thoroughly understand the story and contribute in any way I can.

If I’m brought onboard during the development stage, I offer script notes to the writer or director, regardless of whether they accept them. Sometimes, an editor can provide profound script notes that can fundamentally alter the course of a story. If I participate in the pre-production stage, I assist with the design of shot lists and edit video storyboards to provide a preview of the film.

If I start during the production stage, I diligently review the dailies after each day’s shooting. I start editing immediately, experimenting with scenes, spotting continuity issues or gaps in coverage, and relaying these observations to the director so that they can plan for pickups.

Steven Spielberg famously said, “Editing is synonymous with directing.” While it might often seem like a solitary and autonomous job, its influence and power are significant, especially if you’re brought on board early during development.

While it’s often beyond my control how much influence I can exert outside of my editing role, my passion and commitment to doing the best job possible motivate me to contribute as much as I can. My experience has shown me that these contributions, regardless of their scale, can substantially benefit both the film and the show.

When it comes to editing, I always follow my heart and tell the truth to myself and my collaborators. However, it’s crucial to let go of the ego that makes you believe that your choices are invariably correct. Even if you’re convinced that a director’s or producer’s idea for a cut is wrong or ridiculous, always be open to trying it out.

Surprisingly, many notes that initially seem unsound can turn out to be great ones. If the suggestion turns out to be truly ineffective, the director or producer will usually see this and be convinced to consider your choice. Maintaining a delicate diplomacy in the editing room is critical for the smooth running and longevity of the post-production process.

How do you approach your work as an editor, and what do you think sets your work apart from others in the industry?

As I often emphasize, the first duty of an editor is to understand the story thoroughly. An editor’s role can be compared to that of an orchestra conductor, leading the ensemble to deliver harmonious music. If an editor fails to understand the story fully, it’s like a conductor misreading the sheet music and leading the orchestra offbeat, disrupting the whole performance.

Without a comprehensive understanding of the story, the editing process can generate a ripple effect of issues – the tone might be wrong, the pace and rhythm may be too fast or too slow, the choice of coverage could be off, the music might not fit, and so on. Ultimately, the film may not align with what the filmmakers envisioned.

Many novice editors focus on the techniques and styles of editing to make the film look or sound “cool.” But when the film’s edit seems off, it’s usually not because one or two cuts are wrong. More often, it’s because the editor didn’t fully understand the story, which determines the correct execution of the entire edit.

For any project I undertake, whether it’s a commercial, a short film, or a feature, my approach is to start by reading the script, analyzing the tone, and dissecting and digesting the story. This process is like absorbing the project’s DNA, which can prevent potential problems in future edits. I also prefer to maintain close communication with the director and other collaborators.

While editing can often be an autonomous job, it remains part of a team effort in filmmaking. I believe that harmonizing the editor and the director, both in ideas and communication, is key to the efficiency and ultimate success of the editing and post-production processes. When the editor can quickly understand and implement the director’s notes and the director can readily digest and accept the editor’s advice, they become a powerful team. This dynamic duo, akin to skilled snipers, can aim and shoot effectively to fulfill the mission.

The works I’ve edited vary in style and tone, but they all explore human themes of trauma, grief, growth, or redemption, often tied to a social cause. I believe filmmaking holds the responsibility to advance societal progression and public enlightenment by portraying humanity in various conditions. That is my credo for the types of films and content I strive to create.

If my films can inspire someone to walk out of the theater with a changed heart for the better, then I feel I have fulfilled my duty.

How do you stay up to date with the latest technologies, techniques, and trends in the film industry, and how important do you think it is to continue learning and evolving as an editor?

As an editor, I live in a rapidly evolving technological society where staying abreast of advancements and trends in the film industry is more than a mere asset. It’s a necessity. The tools of our trade – NLE software, computers, and other associated equipment – form the backbone of our creation and work processes. Anyone familiar with the industry knows how changes and updates in technology can fundamentally reshape our workflow. Especially with the swift rise of AI, the future of our job and industry could be significantly impacted.

In the bygone era of traditional film, editing was an analog and mechanical job. Today, with powerful creative software at our disposal, we can perform myriad tasks with dramatically increased efficiency. This evolution has reshaped the qualifications and demands of our profession compared to past generations of editors. Filmmaking has always been a blend of art and science, and like any other human endeavor, it’s continually evolving under the momentum of unstoppable forces.

Staying updated with the latest technologies and techniques, and adapting to trends, is the only way to ride this wave rather than being overwhelmed by it. After all, as with any artist throughout history, we must first master our tools in order to create.

Can you talk about a particularly challenging project you worked on as an editor and how you overcame the challenges?

My thesis film at AFI Conservatory, CHORUS, proved to be a challenging but ultimately rewarding project. I collaborated closely with the director, refining the film to best align with the script. We screened our work for our cohorts and mentors, receiving largely positive feedback. However, two scenes were consistently pointed out as being too long or redundant. Our primary task was to address these scenes. The film’s story revolved around a father and son who missed their wife’s/mother’s farewell phone call on a 9/11 plane, exploring their ensuing journey of grief and healing.

The problematic scenes were one where the father goes to a cake shop to pick up a birthday cake for his wife’s birthday anniversary and another where he and his son celebrate with his parents-in-law at his house. Our first strategy was to shorten these scenes. We made careful edits, removing unnecessary parts or beats without compromising the narrative. However, even after this surgical pruning, new audiences still felt disconnected from these scenes.

We then had to make some difficult decisions, eliminating parts of the story that didn’t transition well from script to screen. Dissatisfied with the overall impact of the cake shop scene, the director decided to remove the scene completely. It’s always hard to ‘kill your darlings,’ but sometimes it’s a necessary part of the editing process. This decision proved fruitful as the narrative flowed naturally without this scene, and we saved around three minutes of screen time.

The scene involving the grandparents required more nuanced editing due to its role in exposition and narrative progression. We meticulously pared down this scene, consulting with my editing mentor who offered a valuable insight: “You don’t need to reveal the entire scene or dialogue to deliver the information.” With this perspective, the director and I opted to cut the main dialogue in half, eliminating all the set-up dialogue from the first half of the scene. While it seemed radical at first, the approach worked exceptionally well.

In subsequent screenings of this revised cut, viewers no longer identified issues with pacing or redundancy. Presenting half of the dialogue effectively conveyed as much information as the full scene but did so in a more concise and straightforward manner. In editing, less is often more. With this philosophy and approach, we managed to reduce the film’s run time from an initial 30-minute cut to a 20-minute picture lock cut, achieving a transformative 10-minute reduction that significantly improved our film.